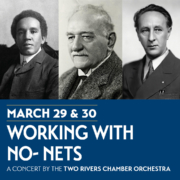

Carlos Simon

Carlos Simon

(Born in Washington, D.C., in 1986)

Elegy: A Cry from the Grave

The American composer Carlos Simon, who was born in Washington, D.C., and raised in Atlanta, Georgia, is one of the most popular musicians and composers working in the United States, with a similarly growing reputation around the world. He is curretly the composer-in-residence for the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, as well as being an associate professor at Georgetown University, in Washington, D.C. Simon’s career as a composer has been boldly advancing for more than two decades, and he has accrued many awards and honors. In 2023, he received a Grammy nomination for Best Contemporary Classical Composition for his album, Requiem for the Enslaved. Simon is extremely prolific, writing in a host of genres for chamber, choral, and orchestral ensembles as well as film soundtracks, many of them on commission. His compositions are often powerful reflections on social issues, with a prominent focus on Black Americans’ struggles for equality. He told the Washington Post recently,

My dad, he always gets on me. He wants me to be a preacher, but I always tell him, “Music is my pulpit. That’s where I preach.”

Simon’s Elegy: A Cry from the Grave was written in 2015 as a personal protest and seeks to bear witness to injustice, as Simon explains:

This piece is an artistic reflection dedicated to those who have been murdered wrongfully by an oppressive power; namely Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, and Michael Brown. The stimulus for composing this piece came as a result of prosecuting attorney Robert McCulloch announcing that a selected jury had decided not to indict police officer, Daren Wilson after fatally shooting an unarmed teenager, Michael Brown, in Ferguson, Missouri. The evocative nature of the piece draws on strong lyricism and a lush harmonic character. A melodic idea is played in all the voices of the ensemble at some point of the piece either whole or fragmented. The recurring ominous motif represents the cry of those struck down unjustly in this country. While the predominant essence of the piece is sorrowful and contemplative, there are moments of extreme hope represented by bright consonant harmonies.

The opening bars begin with the feeling of quiet, cold winds stealing through the air, as the upper strings rustle in tremolos marked to be played Sul ponticello, a musical direction to bow very close to the bridge, creating an eerie, hollow sound. This ghostly aura becomes even more ethereal as several of the strings make portamenti (small slides) between pitches. Above that, the central melodic idea soon arises in the violas. This melodic idea is an angular motive with several wide intervallic leaps, and yet it’s darkly lyrical, evoking the feel of a wounded soul singing out with passion and representing the crying out of those unjustly killed, which will be spoken by an increasingly angered chorus. The upper strings quickly respond with this same melodic idea, while the lower strings then continue the eerie tremolos. And from this sound bed, the melodic idea finds its way into every voice in the ensemble, often moving in tandem, or in harmony, or in polyphonic complexities. And yet, in the building of this chorus, Simon creates many moments of sheer beauty that shine spotlights of hopefulness. The exquisite harmonies that the lower strings create at only 30 seconds into the work is but one of these many beauties.

Eventually and inexorably, the voices build up to an anguished climax at about four and a half minutes, when every instrument breaks into a loud, aggravated tremolo. From here, the music recedes into quieter and quieter iterations of the melodic idea, like ebbing anger faintly illuminated by hope.

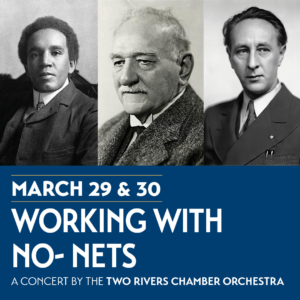

Eric Nathan

(Born in New York, New York, in 1983)

Double Concerto for Solo Violin, Solo Clarinet, and String Orchestra

The American composer Eric Nathan has received many prestigious awards and grants, including both Guggenheim and Rome Prize fellowships and a Charles Ives Scholarship, and has become a celebrated voice in the international musical scene. He is an associate professor of music at Brown University in Rhode Island and serves as artistic director of the Boston ensemble, Collage New Music.

Nathan wrote his Double Concerto for Solo Violin, Solo Clarinet and String Orchestra in 2019 at the request of both the New York Classical Players and the New England Philharmonic. And he wrote it specifically for our concert’s soloists, Stefan Jakiw and Yoonah Kim. The work is dedicated to them, and they performed its premiere in 2019 (and married each other during their preparation for the premiere).

Nathan describes this work as a “relationship” between its players that dramatizes “an emotional transformation”:

At the heart of Double Concerto is a focus on the relationships between our three main characters — the two soloists and the string orchestra. Some of my thinking on the roles these characters play grew out of early conversations I had with Stefan Jackiw and Yoonah Kim, the two soloists for which this piece was composed, and is dedicated. Jackiw described thinking of the role of the clarinet in string chamber works, such as Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet, as an invited guest. In my Double Concerto, we begin alone with our protagonist, the violin, and the string orchestra, which acts throughout like a chorus from Ancient Greek theater, standing in solidarity with the soloists and narrating and personifying the internal or external struggles they face. The solo clarinetist does not enter until almost halfway through the work, but when it does, it unexpectedly alters the course of the concerto, perhaps also instilling hope when it is most needed. The work, cast in a single movement, follows an emotional transformation.

The orchestra opens the concerto by playing long, static pitches evoking a vast and desolate landscape. The violin soloist then enters with a slowly rising passage that’s both beautiful and lamenting. As the violin weeps, a series of descending glissandi (long slides) occur in the orchestra, creating an eerie and surreal effect as though, in the inky black of the night sky, the canopy of stars begins to fall. This weeping-wandering continues until about two and a half minutes, when the soloist plays a rather resolute passage that finishes by reaching upwards with three long pitches, each just a bit higher than the last. This motive will reappear several times in the concerto, and Nathan describes it as an idée fixe — a musical phrase that reoccurs at important moments.

After some darkly turbulent music, the violin climbs back up to its earlier high perch in pitch — meanwhile, the clarinet has been waiting silently for six minutes. From niente (nothingness) the clarinet enters here, joining the violin’s stratospheric pitch, and grows in volume from a tiny ray of light into pearlescent radiance. The violin responds with its idée fixe, to which the clarinet replies with growing resolve, seeming to lead the violin out of its gloom with an increasingly assured tone. As it does so, a remarkably beautiful accompaniment occurs. Here, Nathan borrows from one of Bach’s Twelve Little Preludes (1720s), a tutorial that Bach created to teach his son, Wilhelm Friedemann, how to play the keyboard. Nathan sets the basic chords of the collection’s first prelude (BWV 924 in C Major) as the orchestra’s accompaniment to the clarinet’s ruminations, and the appearance of such unexpected tonality is breathtaking. This, however, soon creates conflict with the violin, sparking a virtuosic madness of rhythms and volume.

When calm returns at about 13 minutes, the clarinet begins an unorthodox cadenza. Instructed to play “encouraging, teaching,” the clarinet sings small parts of the violin’s idée fixe. And at the end of each fragment the clarinet holds the last note, inviting the violin — “teaching” as Bach had done with his preludes for his son — to join in that note, which the violin does with touching vulnerability. The final bars are directed to be played “floating, timeless, blending,” and this fascinating, moving concerto then deliquesces into its final, healing silence.

Aaron Copland

(Born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1900; died in North Tarrytown, New York, in 1990)

Concerto for Clarinet and String Orchestra (with Harp and Piano)

1. Slowly and Expressively Cadenza

2. Rather Fast Coda

During the 1930’s America’s taste in popular music was all about “Swing” music (as Jazz was called then), which was played on the radio, on play-at-home records, and in local dance halls. One of the greatest Swing bandleaders in that era was Benny Goodman (1909–1986) who was also a phenomenal jazz clarinetist. But during World War II and later in the 1940’s, American tastes changed as Swing gave way to the “Bebop” jazz of Charlie Parker and Thelonius Monk. Goodman changed, too, and so began his second career as a classical clarinetist but with a jazz inflection. It was in this new role that in 1947 Goodman commissioned a concerto for clarinet from the greatest contemporary American classical composer, Aaron Copland.

At this time, Copland was lecturing and conducting in Brazil, where he created most of Goodman’s concerto. Copland infused the work with an ear towards Goodman’s hallmark jazz, while also weaving in aspects of popular Brazilian music — almost unconsciously, he said. The concerto was premiered to great acclaim in 1950 in New York, with Goodman as the soloist, and it quickly became a beloved fixture in the clarinet repertory.

The concerto is conceived in an unusual structure with only two movements, one slow and one fast, connected by a long clarinet cadenza. As accompaniment for the soloist, Copland relies on a sparse orchestra of strings, harp, and piano. The first movement, marked “Slowly and Expressively,” begins with the open and glowing simplicity of plucked basses and harp, and as the remainder of the strings slowly join in, the clarinet starts singing a meandering, intimate song. This first movement progresses through some exquisite harmonies under the singing clarinet as it enchants us with its exceptional lyrical abilities and extraordinary range.

At about six minutes, the music quiets considerably, and the soloist begins a two-minute cadenza. At first, the feeling is pacific, but soon the mood changes dramatically, shot through with increasingly frenetic passages. Within this lengthy cadenza, Copland shows off the clarinet’s remarkably athletic character, while also introducing many of the motives that appear in the next movement, which begins without any pause.

This second movement, marked “Rather Fast,” begins with the harp plucking, the stringed instruments playing harmonics and tapping their strings with the wooden end of their bows, and the piano playing short, soft notes, directed to be played “staccato, delicate, and wraith-like [like a ghost],” evoking a kind of mischievous, apparitional music box playing at high speed. This movement focuses on short ostinatos and riffs — little syncopated phrases that repeat –– and which are constantly changing. This is jazz in classical clothing and Copland employs ever-more jazzy elements throughout. He explained, “I used slapping basses and whacking harp sounds to simulate [jazzy percussion effects],” which you can hear at about three and a half minutes after the start of this second movement.

Evocations of Brazilian popular music start to show up in this movement as well: the first appearing only a few bars after the “slap-bass” begins, where Copland inserts a very singable little tune in the clarinet, rising up in steps and then coming back down, and then a second one appears about 30 seconds later with a little noodling run upwards, first heard in the strings, then the piano, and followed by the clarinet. The music, however, gets increasingly intense and filled with disorienting syncopations until, at about three minutes later, a pounding, descending bass line in the piano begins, launching the Coda (ending section) and setting off a melee of excitement. This masterpiece concerto nearly hurls itself to its final bars, jubilantly ending with “a clarinet glissando — or ‘smear’ [in jazz lingo].”

Giuseppe (Fortunino Francesco) Verdi

(Born in Roncole, near Parma, Italy, in 1813; died in Milan, Italy, in 1901)

Prelude to Act III from La Forza del Destino (“The Force of Destiny”)

In 1861, Verdi received a commission from the Imperial Theater of St. Petersburg, Russia, for a new opera. As he had with Nabucco and many of his previous operas, Verdi turned again to a loosely veiled theme of Italy’s current struggle for independence and unification that had consumed much of the 19th century. He also returned to one of the great librettists of the day, Francesco Maria Piave (1810–1876), a longtime friend and librettist for nine of Verdi’s previous operas. Piave based the text for Verdi’s commission, La Forza del Destino (“The Force of Destiny”), on an 1835 Spanish drama, Don Álvaro o la fuerza del sino (“Don Álvaro, or the Power of Fate”), by the Spanish Enlightenment author and politician, Ángel de Saavedra.

La Forza del Destino follows the plight of two ill-fated lovers, Álvaro and Leonora, set in 1740’s Naples. The opera begins with Álvaro and Leonora being hopelessly in love, but Leonora’s father, a Spanish dignitary, cannot accept Álvaro’s “half-caste” Peruvian-Incan blood as a sufficient lineage for his daughter, and so, the two lovers attempt to elope. The father discovers their plan and confronts them, and during the heated exchange Álvaro’s gun accidentally fires and kills the father. Thus is set into motion the current of Fate — an inexorable sequence of tragedies — that will dog the steps of the two lovers forever.

The opening of Act III takes place in the pitch of night, in a forest near Velletri, Italy, where, in fact, an important battle took place in 1744 between Spanish-ruled Naples and the Habsburg Empire. Álvaro has joined the Spanish-Neapolitan army and is camped with his regiment before the battle. He and Leonora have been hiding separately for some time, and without any word from her, Álvaro presumes she has died. Act III opens with martial music as soldiers rowdily play cards offstage. A forlorn Álvaro slowly and silently advances into the light, and he will soon reflect on his life that has been hounded by bad luck, crowned by the most recent tragedy of having lost his beloved Leonora. But before he sings, a musical prelude sets the tragic tone with exquisite beauty.

In the prelude, the strings shudder quietly in tremolos of tattered nerves and tension, and the clarinet begins with one of Verdi’s most famous solos for that instrument. Verdi often features the clarinet in La Forza del Destino (in fact, a former student and friend was the principal clarinetist of the St. Petersburg Opera). Considered to be an instrument that best resembles the human voice, the clarinet in this prelude creates a kind of psychological inner landscape of Álvaro’s tortured soul. Slowly at first, the clarinet sings a tune that is beautiful, but also wistful and pained. After a few bars, the horns alone softly play three ominous notes in unison, which is Verdi’s “Fate” motive that reappears throughout the opera. The clarinet sings again, but now with an even more beautiful and melancholic tune which will then become the tune of Álvaro’s subsequent aria. The clarinet’s singing soon branches out into small cadenza-like reveries, reflecting Álvaro’s tender hope that Leonora is now in the care of angels. But eventually, the lower strings begin a quietly menacing pulsing that scatters the clarinet’s ruminations, and as the clarinet plays its last, touching notes, the strings end this prelude with a series of upward steps, as though Álvaro is climbing out of his own tormented heart. Act III then moves on to feature Álvaro’s aria, but for the moment, the clarinetist has been the shining operatic star, having delivered a series of potent, heart-catching solos.

Felix Mendelssohn

(Born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1809; died in Leipzig, Germany, in 1847)

Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. posth.

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Allegro

Mendelssohn’s upbringing was filled with privilege and took place in perhaps the most artistically and intellectually stimulating environment of any musician of his time. Besides receiving near-continuous visits from many of Europe’s most influential thinkers and artists, the Mendelssohn family hosted a Sunday morning musical salon for their latest guests, featuring young Felix and his sister, Fanny, performing music and showing off their own compositions. Nevertheless, there is no argument that Felix was, on his own merits, one of the greatest musical prodigies in history. Even before composing at the age of 16 or 17 his extraordinary String Octet (1825) and his Overture to a Midsummer Night’s Dream (1826), Mendelssohn had already created 12 symphonies for strings; multiple sonatas for violin, piano, and organ; several lieder (songs); two short operas; a cantata; and in 1822, this violin concerto in D minor.

This D minor violin concerto should not be confused with Mendelssohn’s later, and hugely beloved violin concerto in E minor that he wrote near the end of his life, in 1845. This earlier Concerto was written to be performed by his violin teacher, Eduard Rietz (for whom Mendelssohn also later composed his String Octet as a birthday present), but it never made it into the family’s Sunday morning salons, and there is no record of it having been performed elsewhere during Mendelssohn’s life. In fact, the concerto was virtually forgotten until 1951, when a rare-book collector, a descendant of Mendelssohn’s, presented it to the great violin virtuoso, Yehudi Menuhin. Menuhin premiered the Concerto in 1952 at Carnegie Hall, and slowly, this lovely work has been gaining a reputation as Mendelssohn’s marvelous “other Concerto.”

Written for violin soloist with string orchestra, Mendelssohn begins the first movement, Allegro, with the full orchestra playing a theme that cavorts with quick runs and clipped rhythms dancing up and down the scale. Though the minor key adds a sinister hint to the music, the theme nonetheless wanders into a series of somewhat playful cat-and-mouse exchanges between the upper and lower strings. The violin soloist enters at about one minute and a half with a new, more lyrical and melancholic theme, which quickly demands virtuosic runs. Virtuosity and lyricism, for both the soloist and the orchestra, then alternate in delightfully inventive ways until the end of the movement.

The second movement, Andante, is filled with tenderness and lyricism that feels uncannily mature for a 13-year-old composer. The violins begin with a slow and unpretentious theme, quietly climbing up the scale and then gently tumbling down. Behind them, the basses and violas echo that theme in a sort of canon that creates a sense of yearning. When the soloist enters about two minutes later with a short little cadenza, that yearning is intensified. The soloist then moves into a new theme composed of several measures of long, lyrical notes that periodically give over to more active rhythms, like a jittery love-smitten heart. The entire Andante explores these emotions in a number of gentle ways, until the last beautiful bars, where the soloist sings alone, quietly holding a note high in its register.

Without a pause, the fiery third movement, another Allegro, begins. The soloist and orchestra jump in together with a theme that’s free-spirited and frisky. The soloist quickly launches into virtuosic passages, which are often answered with equally virtuosic playing in the orchestra, and together they soon arrive at a series of cadenzas for the soloist that were written out by the young Mendelssohn. The rest of the movement then sprints away as if on a precipice, with an exhilarating feeling of coming dangerously close to slipping off the edge. As the soloist performs with increasing pyrotechnics, the movement comes to its exciting and wonderfully fun final bars.

© Max Derrickson

Introduction – Regarding Nonets

Introduction – Regarding Nonets

Introduction

Introduction

Henry Cowell

Henry Cowell

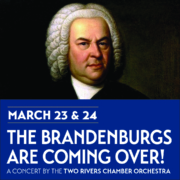

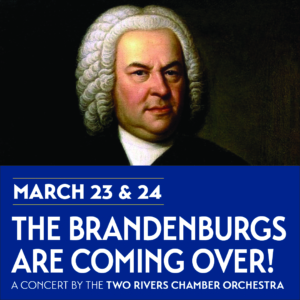

Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach

György Sándor Ligeti

György Sándor Ligeti

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges